The prior minister in my current role, I was told, did not have the infrastructure or emergency funds to sustain a portfolio of loneliness. The authorities simply noted that isolation in the year of quarantine is palpable; it has taken on catastrophic proportions comparable to the plagues of ancient days.

Frankly speaking, the ministry position is a file shuffling job in a virtual sense, a documenter of records and data on the correlation between the Great Panic and the psychological effects of isolation. A glorified clerk, more than a minister, if you will. It’s not a role that involves the abatement of loneliness.

Rather, the minister is a processor of loneliness, and sort of bureaucrat, if you will. The Minister of Loneliness is not a counselor of lonely hearts or other such romantic fancies. The invitation for the job arrived over the invisible transom, thanks to the information brigade with its bits and bytes of data, an invitation which I scoured in a compulsive yet amateurish manner to pass the hours of sheltering in place.

The analysts of yesteryear used to say, geography has nothing to do with leaving behind your negative experiences; the abyssal terrain of memory will follow you like the tail of a runaway gecko. You see, I don’t mind living a small life. I’m not called to settle the moon. Despite the dire warnings of our virologists and epidemiologists, we lived close together in the urban zones across the world, cocooned in an illusion of safety, ignoring the early signs of the Great Panic. Years ago, in the migrant generation of my grandparents, the nations each sent a colony of people to settle the moon. Admittedly, it was a failed experiment – the colonists were sickened by the poor air supply, and thousands perished in the biodome. It was neither a viable solution for overpopulation, nor a feasible strategic investment in human life as we knew it, but rather, a stupid plan to purge humankind of all diseases, in other words, a gene genocide.

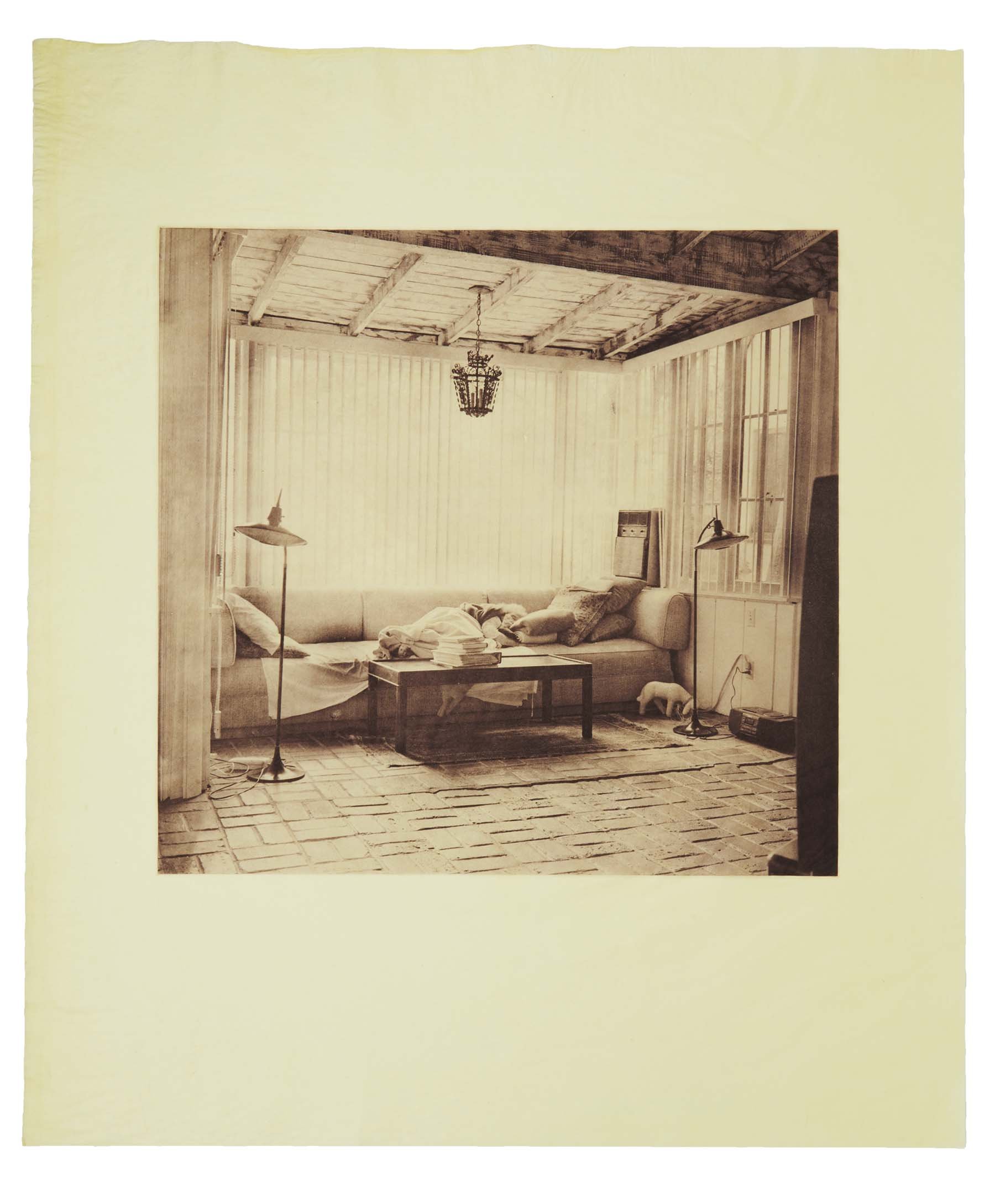

As the Minister of Loneliness, I look at the stars not as a program for my life, but as signs of a creator who placed each little fire in the heavens. To remind myself about the life before the Great Panic, I write a list of activities I used to relish. If the Minister of Loneliness can’t handle solitude, then how will she process loneliness during the Great Panic? By mirroring what I’m hearing and listening to what’s not said; untying the knot of each irrational fear by asking questions; pointing at jars of olives and sweet pickles at the open-air market; shaking hands with strangers at the bus stop, or vice versa.

In a quarantine dream, the world and its pantries of abundance have reopened with a global puff of flour, pouring a wealth of refined wheat and sugar into the world. I bake a chocolate cake out of a box, scissoring the bag with puff of dehydrate, powdered buttermilk, flour, and cocoa. I use eggs, extra virgin olive oil, and a quarter cup of bottled water to moisten the cake flour. I pour it into nine-inch cake pans. After the cakes have cooled, I frost them with a tub of whipped cream, and sprinkle half a cup of shredded coconut, a quarter cup of chocolate shavings, and chopped strawberries. I had no one to enjoy the cake other than myself, so I put it in the basket and lower it on a rope to the street. Partway down its journey, the ashen mourning doves of the city emerge to consume mouthfuls of the cake until none of it remains by the time the bucket touches the sidewalk. The mourning doves, cooing with grateful contentment, swoop up in flock and circle above the rooftop before flying back to their nests tucked in the nooks and crannies of the city.

I assemble a blackberry fruit tart with a buttery, flaky crust made from a tin of shortbread cookies I find in the back of a cabinet, and it’s the green parakeets who receive the blessing, then the crows, ravens, and grackles for morsels of the pistachio ice-box pie made with a graham cracker crust and a pudding mix folded into whipped cream. The glossy cream cheese and guava jelly crescent rolls were the favorite of the pigeons, and the mockingbirds swooped upon the hot cross buns made with a brioche dough. The organic strawberries fattened by alfalfa meal, by the way, were big as my fists, mashed to a bloody pulp in the mouths of feral parakeets. When I wake, the world is still on fire with a massive infection, and there is no place to run from the phobias contributing to the Great Panic. Each individual must go on lockdown, sheltering in place to avoid breathing on others until the world opens up again.

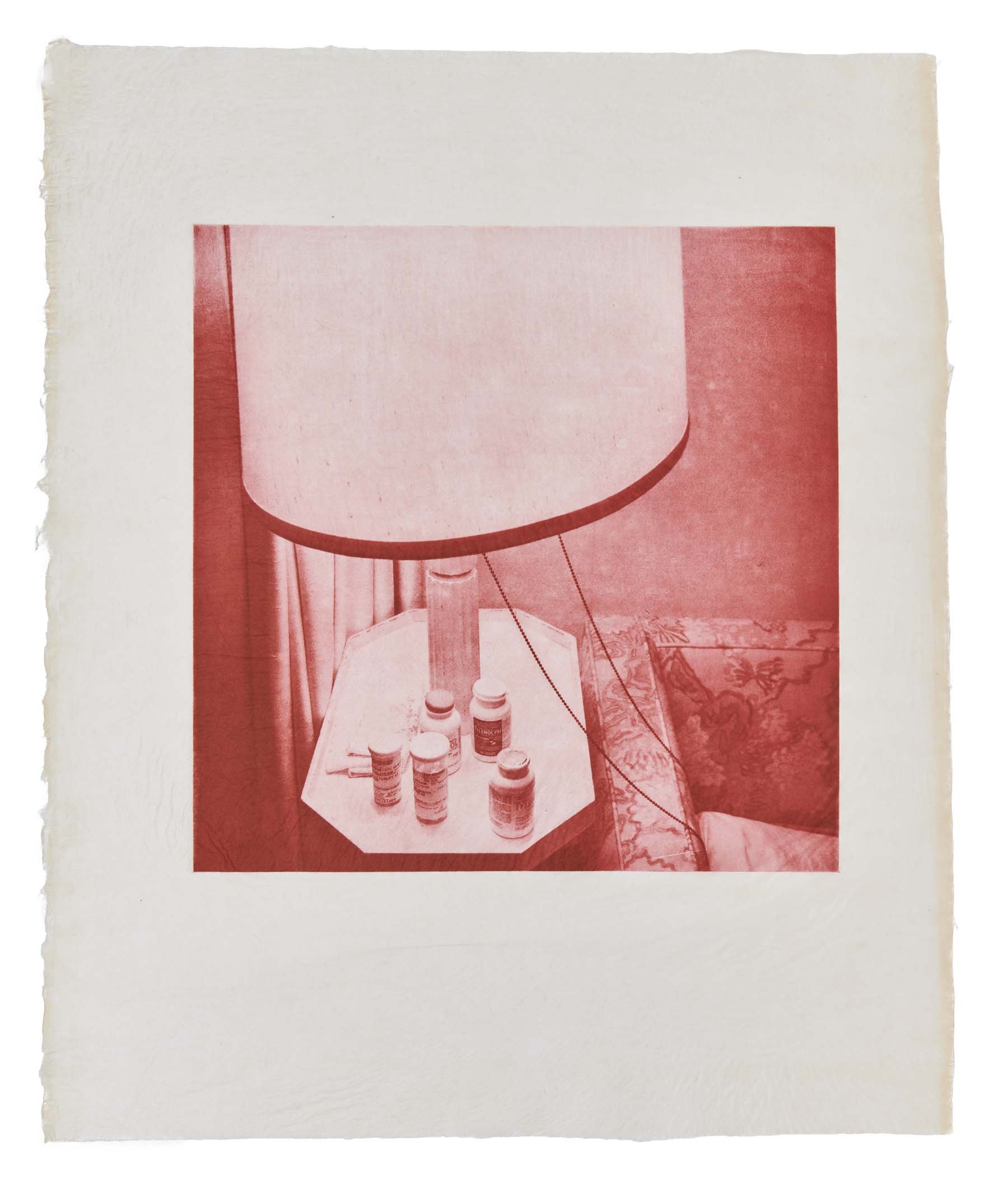

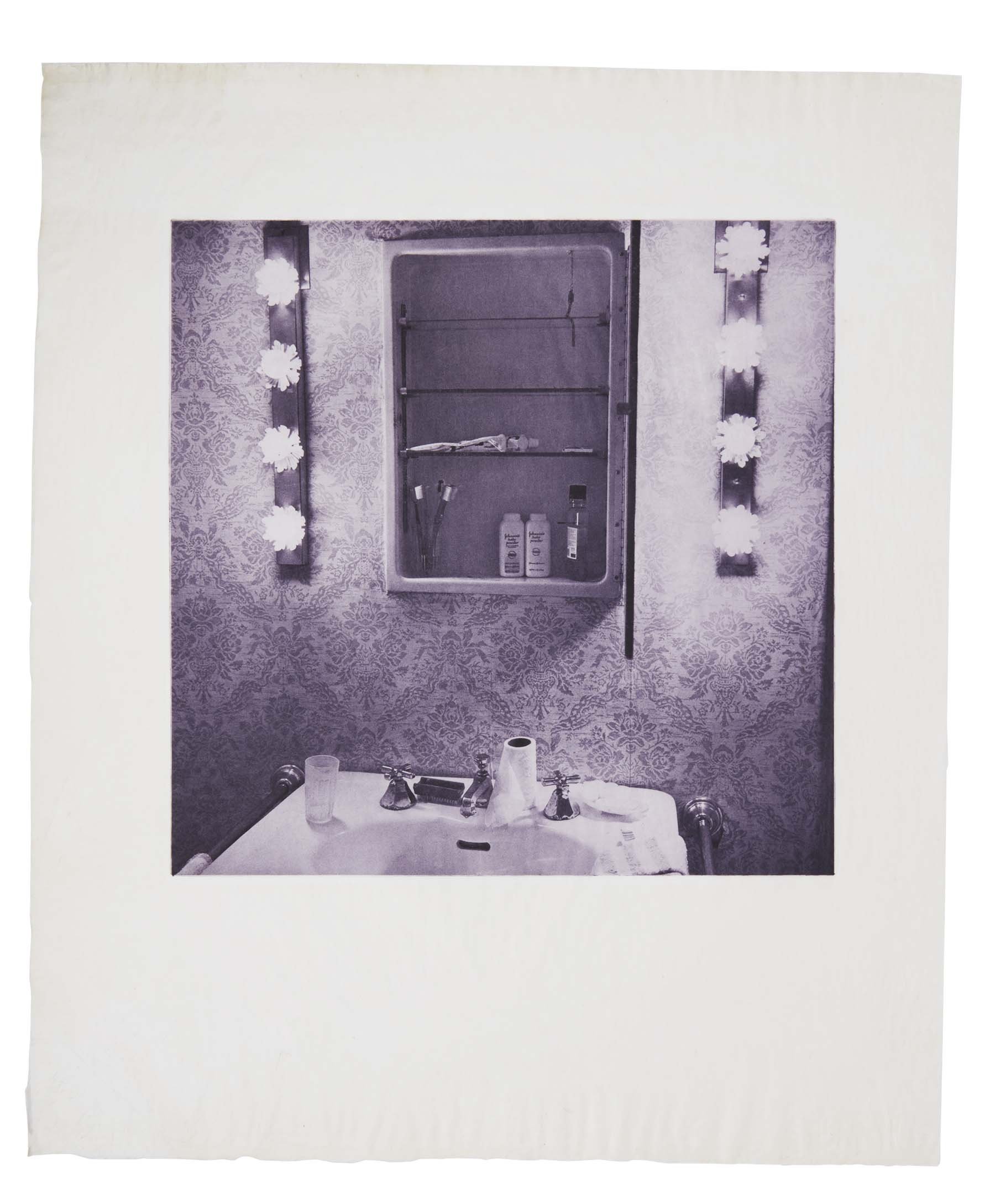

In the ministry of loneliness, with my parish of none, I go incognito by turning off the information brigade, the only endorsed chatter in the lockdown. If I don’t hear about it, I am not responsible for it. The weather is hot and dry as midsummer. In the night, I wake with a sore throat, the right tonsil precisely speaking, and look up the possibilities of what this might mean. A bacterial infection like staphylococcus, infected tonsil with tonsillitis, a tonsil with tonsil stones, or soft uvula abrasion from loud snoring? At the back of my mind, I’m aware this could mean I harbor the contagion of fear, lying dormant and asymptomatic in my body, now surfacing as tonsillitis, grazed lightly by a silver spiral of fear. I try ice cream first, then hot milk and honey to coat my throat, anti-inflammatories, and finally, daub the back of my throat with a mixture of aloe vera, oregano oil, and antibacterial ointment in a base of petroleum jelly. With a flashlight to the back of my mouth, I could see the telltale inflamed tonsil peeking out like an angry cockscomb out of the corner of my gullet.

For decades, it was the fear of a generation who suffered aviophobia, a fear of airplanes, and now the little children do even not remember their parents warning about it, and how the parents of their parents recall the images of planes falling on their vintage television sets and splashed across the pages of their newspapers, the plumes of smoke rising out of the twin skyscrapers. Do you remember where you were, what you were doing? Yes, I was speaking with my mother on the phone, the landline, not a mobile device, and she dropped the phone in the dish washer. No, I was getting ready for school, putting my bologna sandwich in my backpack. It was not yet the age when we could livestream events. The morning news anchor was not his usual chipper self, while the newsroom behind his head showed a whirlwind of people and papers in chaos. Now the fear has dissolved into the generalized routines of the populace, especially when we use documents to identify ourselves, and we remove our shoes for flights. How do we demonstrate who we truly are in an age of dissociation, of likes and dislikes popping up like assorted gumdrops and lollipops?

In the Great Panic, I can’t help thinking of the bird pneumonia carried by feral urban birds, not to mention the diseases infecting cats and people. I miss going to the market and picking up an eggplant, then a chayote pear. I miss riding the subway, the lime-colored tunnels of light. I miss the man who played the violin, busking for cash. I miss the for-sale signs propped up inside car windows. I can’t remember the last time I wore heels as I walked in soft-soled flats all over the city. I love flats, my unapologetic flats that say to the world, my soles will be with me the rest of my life, even if they’re unflattering. My flats traveled all over the city of champagne bakeries and chocolate fountains, its dumpling dens and greasy spoons. The city with its clotted cream fog rolling in from the bay and its nightly mood swings from one dive to the next had no idea what await beyond this short season of neon lights. Perhaps short isn’t quite the right word, I muse. Blessed, I whisper, looking down at the stockinged feet I’ve had since the shelter-in-place order began.

Is it too late for the information brigade to design an underground world in cyberspace where bibliotherapists research ancient books of wisdom and poetry as guides for healing, human empathy, and revelation? One where bibliophiles, lovers of books, serve as apothecaries to the drams and draughts of the past? The musty fragrance of the physical books offers consolation in the caves, where consumers of information would slowly pore over the histories and catalogues of yesteryear. Pods of capsules of time, the books would unveil their arcana about making sourdough starter in jars, using aluminum foil and baking soda in hot water to polish tarnished silver, and how to pickle one’s own capers in vinegar and wine, if one wished to do so, those unopened flower buds, the color of avocado flesh under the rind.

A pinking moon like a blushing cheek swooned over the city, a supermoon the color of raspberry lemonade, and for a minute, its witnesses were calmed by its glow. The information brigade, however, reported that it took on a canary tone like tooth enamel while it soared above our sleep. Only in dreams, the pink moon was the color of quarantine, a swirling bottle of the city’s mood in the foaming language of a fountain drink, or a glass of hibiscus tea spilling into the nocturnal clouds. The Minister of Loneliness picks up a spy glass, a brass, one-eyed telescope of sorts, and points it at the moon to see if it is a glass of pink lemonade.

Nope. In the rays of the moon, I dream of a labyrinth of honeycomb tunnels where the Minister of Loneliness is quarantined, a raindrop of vaccine against fear itself flashing its golden, quadrivalent eye in the lights at the end of every passageway, targeting flu strains cultivated in cell cultures, not in millions of eggs laid by government chickens. For this elixir of immunity, the vaccine is dyed red as prosperity eggs, as if prepared for a baby’s one-month birthday, when her name is finally announced to the world. Let us rejoice, for this child has survived a full month and beat the odds of death itself, at least, for now: her immune system has fought off the bacterial strains and toxic nitrites in the underground well water, the cross-contamination of a bovine caseinate formula boiled in a kitchen pot, the hands and feet of many relatives in the nursery. On a scrap of a paper bag, I write out a gratitude list starting with unbleached bread flour.